Book Review: Humankind

- The Educated Idiot

- Jan 3, 2021

- 10 min read

An old Cherokee is teaching his grandson about life. “A fight is going on inside me,” he said to the boy. “It is a terrible fight and it is between two wolves. One is evil – he is anger, envy, sorrow, regret, greed, arrogance, self-pity, guilt, resentment, inferiority, lies, false pride, superiority, and ego.” He continued, “The other is good – he is joy, peace, love, hope, serenity, humility, kindness, benevolence, empathy, generosity, truth, compassion, and faith. The same fight is going on inside you – and inside every other person, too.” The grandson thought about it for a minute and then asked his grandfather, “Which wolf will win?” The old Cherokee simply replied, “The one you feed.”

Most of us would acknowledge that we as human beings are capable of going either way - we have the ability to do good, as well as the ability to afflict harm. But take a survey of any random sample of people, young or old, rich or poor, educated or uneducated, and they would probably tell you that human nature has been hardwired in such a way that we would definitely tend towards self-serving opportunism rather than magnanimously serving the good of our kind. Prima facie, we live in a world where the cynic is always right. If one sees acts of selflessness and generosity, we instinctively assume that it only masks some selfish agenda. Helping an elderly lady cross the street? What a show-off! Donating money to the homeless? Probably only wants to feel better about himself! In the news, as one would know from my review of Stop Reading The News, the bad is overreported and overblown, while good news like innumerable people being lifted out of poverty is obscured. If the news is bad, books should be a wiser respite, right? Even there, most books document the worst sides of humanity. History books focus on conflicts, catastrophes and Machiavellian intrigue. Science books offer the gloomiest theories of evolution. Economics books define our species as homo economicus, portraying humans as rational agents who are narrowly self-interested, pursuing their subjectively-defined ends unfalteringly. Religions like Christianity espouse that we are born sinful and do not offer any less grim a view of human nature. Above all was the philosopher Thomas Hobbes, who famously exclaimed that the condition of man is a condition of war and described life as short, nasty and brutish.

Most of us may resonate with this “cynical” view of human nature, which comes all too natural to us. But not Rutger Bregman. He instead puts his faith in Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who famously declared that man was born free and it was civilisation – with its coercive powers, social classes and restrictive laws – that put him in chains. While Bregman does not claim humans are angels, he espouses the idea that human nature is fundamentally good and decent, so we ought to have a more hopeful outlook on the world. For him, our grim view of humanity is also a nocebo. If we want to tackle the great challenges of our time, from climate change to growing distrust, we must begin at the way we see ourselves and each other.

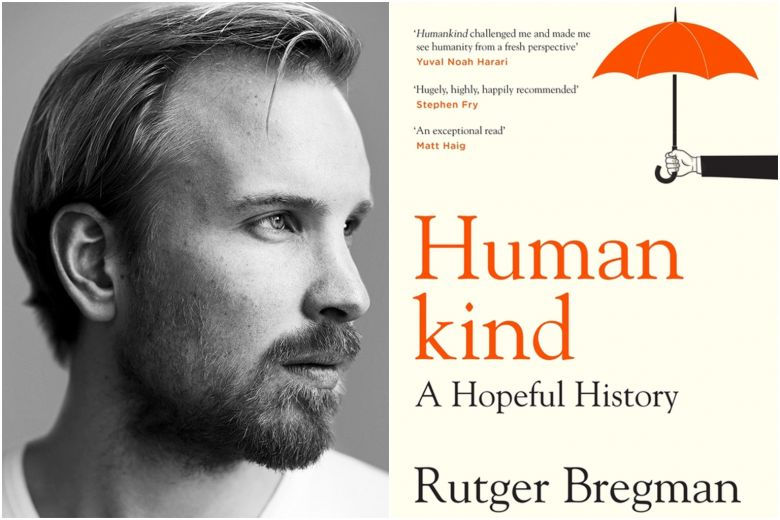

In Humankind: A Hopeful History, Bregman elucidates a variety of arguments, case studies, historical anecdotes, and opinions that seek to convince us of the fundamental kindness and good that we should find in human nature. An argument critical to his thesis is “the curse of civilisation” where he takes a Rosseauist approach on human nature. This view rejects the conventional idea of civilisation as a force of good. Rather, back in the state of nature, before kings and bureaucrats, our hunter-gatherer ancestors were compassionate beings, and archaeological evidence suggests it was a world of less violence, greater equality and liberty. Farming, urbanisation and statehood in fact enslaved and destroyed us. Hierarchy paved the road to inequality, violence increased as we have land and belongings to fight over. The advent of farming decimated leisure time, downgraded the status of women, and deteriorated our physical health. This idea goes head-on against the predominant “veneer theory”, termed by Dutch biologist Frans de Waal, which postulates that our bestial nature could break out any moment and hence we are in need by the Hobbesian “Leviathan” to control us and put us in place, long used to justify the curtailing of freedoms. Even more controversial an argument is Bregman’s view of human evolution. The standard theory we are used to, detailed by Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene, is one of survival of the fittest because we are the most selfish species. We triumphed over the Neanderthals because we wiped them off in the first ethnic cleansing campaign in history. Bregman instead sees human evolution as the survival of the friendliest. We cooperated with each other better than the solitary Neanderthals. And even more interestingly, our friendliness was manifested physically (due to processes occurring chemically) as proven by the Lyudmila Trut experiment, which paralleled the evolution of humans to develop softer, more youthful and more feminine faces to the domestication of dogs that turns a bellicose wolf to an adorable puppy.

Humankind is replete with case studies and historical examples with evidence to back up Bregman’s idea. There is the case of American soldiers in World War II, of whom only 20% of them actually fired their weapons. The remaining majority weren’t cowards or traitors who ran and hid, instead they put their lives in danger to rescue comrades or get ammunition. This is similar to the case of the battles of Waterloo or the Somme, where most bayonets were left unused. In Christmas 1914, barely a year into World War I, British and German soldiers fraternised and called an unofficial truce, in the mood of the festive season and “live and let live”. Such truces were not an isolated case, having occurred before in the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War and the American Civil War. It does seem as if most soldiers weren’t really interested in killing the enemy. And even supposedly evil monsters are also motivated by the good of humanity, as the author gave the example of how the Wehrmacht continued to press on in their losing battle in the closing months of Hitler’s war. They were fuelled by brotherhood, loyalty and devotion to fellow Germans rather than the sinister Nazi ideology. All of this ties into Bregman’s theory on the power of empathy, as many of his examples illustrate a clear pattern that being closer to the enemy lines actually reduces the level of hatred, while most deaths such as from bombings were inflicted from a far greater psychological distance. Looking away from history towards the present, Bregman gives the examples of prisons in Norway, where the guards - 40% of whom are women - share a principle that it is better to befriend inmates than to patronise and humiliate them. The rehabilitative approach has paid off, as the recidivism rate is almost 50% lower, and the likelihood of an ex-convict finding a job is 40% higher. Critics decry it as expensive, something only wealthy Norway can afford, but because ex-convicts commit less crimes, the social cost is reduced, and since more of them find jobs, they rely less on government welfare. Not a naive socialist aberration.

How does Bregman’s thesis and the whole argument hold up? The pattern I observe across the book is that while the evidence provided is correct and indeed detailedly well-explained, but when attributing them to human kindness, the conclusions made can be rather tenuous. The theory of evolution and its links to friendliness that Bregman offers does not actually necessarily dismiss the traditional Darwinian view, and we could very well have evolved this way for entirely separate reasons such as not needing certain features anymore, that does not correlate to kindness. Furthermore, it is ironic that this process of “self-domestication” coincides directly with the epoch of human civilisation that supposedly by the Rousseauist point of view, turned us cynical and self-interested. Looking at the examples given that documented war in history, the examples given are indeed accurate but it simplifies the complex process of fighting war. Most bayonets at Waterloo and the Somme weren’t used, most American soldiers did not fire their weapons, very true indeed but they could be due to reasons beside human kindness and decency. Weapons could very well not be used because in the heat of the battle, there was no need to use them, or the opportunity to strike simply wasn’t present. The Christmas truce? On the Western Front, it was largely an Anglo-German affair, and the French and Belgians certainly did not take part, no least because they had their own territory occupied by the German army. Most deaths being inflicted at a great psychological distance? It could simply because those were the more technologically superior weapons, starting with shells to air raids to atomic bombs. When Bregman attempts an explanation on how terrorists turn evil, he makes mention of the fact of how neighbours and acquaintances describe the radicalised individuals as friendly or perfectly normal, but that does little to explain the complexity of the process and networks that constitute terrorist networks today. And most contentiously of all, is the idea of “The Will To Believe” which I remain highly skeptical of. It stems from the philosophy of William James, who proposed the idea that some things just have to be taken on faith, even if we cannot prove they are true. Take for instance, things like friendship, love and trust that become true precisely because we believe in them. While I can see some merit in such a logic, especially in interpersonal relations, it does not allow faith to triumph over facts that should be objectively looked at regardless of what we would wish to believe.

All this talk about human nature, the good and evil in us, kindness and selfishness, may remain very abstract to many of us. So has it been personally relevant to me, in light of my personal observations and experiences. Do people care about each other? Forget about strangers, just look at whoever we call our loved ones, namely family and close friends. Family, unlike a corporation or an institution whose members can grumble all day about, is not an invention of this “civilisation” that Bregman and Rousseau would refer to as a curse. It would in fact be already an important unit of the state of nature. But does a family work? I would like to believe otherwise, but I am acutely aware that just because I believe does not make something miraculously come true. I would like to think of my family as a happy and caring one, where we get along, look out for each other, and help one another. But is it? I instead have, despite many efforts, a family where communication is limited or stifled, we care largely about ourselves in an individualist outlook, and fighting occurs from time to time. And about my environs? Are people fundamentally nice? Not exactly. For the years I have lived, I have observed that many friendships formed are not genuine no matter how much one “believes” in it. More often than not one utilises the other for pure benefit, and if you suddenly serve no purpose to anyone else, your social value and capital plummets faster than the price of oil. That was the case of myself when I transitioned from a moderately achiever in school to a mere conscript soldier in the army. I saw my social circles decimated, connections torn, friends drifting away. And making new friends a lot harder than I thought, no matter how much one may believe in the idea of camaraderie in the army. And I seem to have seen a very dark side to human behaviour, in a toxic environment where being mean to each other and a culture of shenanigans is not only accepted, but also normalised and even celebrated. It seems like once given the opportunity, people are more than happy to put others down. Is this human nature? How wretched and wicked! Can Bregman console myself and many others in this harsh and difficult world? The best reassurance that Bregman has provided is that all of this is actually a part of the greater curse of civilisation. Or the highest stage of it, no less. Because while nasty behaviour like bullying is often regarded as a quirk of our nature, Erving Goffman asserts that they actually occur most often in “total institutions” that are defined by control, regimentation and a lack of freedom. Such won’t happen if we could actually roam freely in the true state of nature, perhaps?

Well, clearly, while the arguments elucidated by Bregman in Humankind are not weak or unengaging, I am not exactly convinced to look the other way and perhaps adopt a more optimistic outlook for the future. And not just because of personal experiences that would bring more joy to my life to ignore. But because there is so much in history and the world around us today that tells us otherwise. How can one account for the great atrocities of human history, while still telling oneself that humanity is innately a good species? Granted, Bregman provides a fair share of examples and does a great job and detailing and explaining them, but they do not trump what has happened in say, the Armenian Genocide, the Holocaust, or Islamist terrorist attacks. It does not soothe anyone facing the crises of 2021 - a pandemic, a struggling economy, political tension, inequality, climate change and technological disruption. As we enter the new year, I do agree it would be worth having a less negative view of our own humanity, treating each other better and looking the other way with less suspicion in our eyes. On a more personal level, it is worth challenging oneself to rise above this oscillation between good and evil, even if human nature is wretched. And yes, we must acknowledge the effort required to do good if it isn’t in our fundamental nature, but does not render an effort futile. And even if we accept a less than hopeful view of human nature, it should never be used as an excuse for not being our best, for inhumanity or for adopting a fatalistic weltanschauung.

Would I recommend this book? Absolutely, it is a fantastic read, even if you virulently expostulate against Bregman’s thesis. It reads well, the stories inside are well described and documented, and the arguments made are interesting to consider. It has received a fair share of reviews, and other intellectuals like Yuval Noah Harari and Stephen Fry have reviewed it positively, without having to agree. It has not convinced me, that’s for sure, but it does challenge a conventional notion and made me rethink human nature in terms I wouldn’t have prior. Even if you do not emerge as an optimist, you would still most likely emerge with a more constructive worldview than before.

Comments